FONAR: A Microcap MRI Company with a Suspiciously High Yield

There are times when I wonder “what am I missing?” when it comes to an investment, and such a situation is FONAR, a charming very small cap company that based on rough analysis has a free cash flow yield of about 25% when you take excess cash into account (which I do, so there). As with many small cap companies, the founders have tried to keep the company under their control with two share classes, one being publicly traded and the other being privately held by the founders and which have a disproportionate number of votes (25 in this case) as compared to the public shares.

Fonar makes MRIs, particularly “upright” ones that allow the patient to be assessed from a sitting position. However, the bulk of the company’s business is not in the sale of MRIs but in operating various MRI diagnostic centers in New York and Florida. The company owns 6 scanning facilities and operates 38 others, handling pretty much every non-medical aspect of managing the facilities in exchange for a flat monthly fee. Curiously, the company owns only roughly 70% of the facility operations business, with the rest owned by outside investors. The upright MRI that FONAR uses is apparently a niche item, as they are less powerful than the typical one, but apparently they have some useful applications. Curiously, the current CEO of FONAR, Timothy Damadian, is the son of the inventor of the MRI, and also owns three of FONAR’s client facilities, which would normally raise the suspicion of self-dealing but apparently their monthly fees are higher than those of other facilities (although it is possible that the company advantages them somehow (or perhaps they simply run a larger operation than the average facility (I have no evidence on way or another; I’m just speculating out loud))).

What attracted me to the company, however, is that out of its $88 million market cap as of this writing, $54 million of it consists of cash on the balance sheet that has been building up over the last few years, and FONAR apparently sees nothing better to do with it than let it sit there.

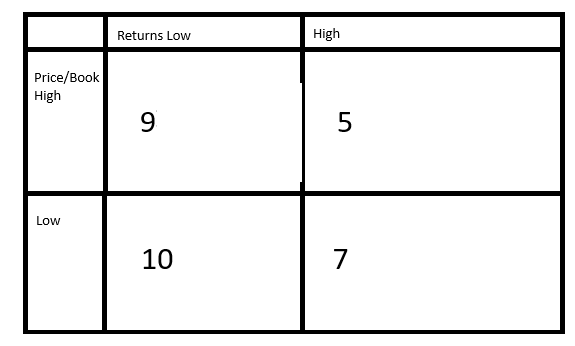

In fiscal year 2025 (ending in June), sales were $104 million, operating income was $11.6 million and excess depreciation was .9 million, leaving $12.5 million in operating cash flow. Interest expense is likely to be negligible as the company has no long term debt, and after estimated provision for taxes this works out to $10 million in free cash flow, minus $2.4 million for the outside investors, leaving $7.6 million in free cash flow to equity, or $6.9 on a fully diluted basis (see below), which based on the company’s equity value minus excess cash is a yield of 20.2%, which is fairly impressive. And this year’s figures were further marred by an outsize $2.3 million credit loss reserve from one particular insurer.

In fiscal year 2024 sales were $103 million, operating income was $16.5 million and operating cash flow was $14.1 million owing to lower capital expenditures and a less extreme credit loss provision. Minority interest allocation was $3.5 million, leaving $10.6 million for the equity.

In 2023 sales were $99 million, operating income was $14.8 million, operating cash flow was $15.1 million, or $12 million after taxes, minus $2.8 for noncontrolling interest, leaving $9.2 million for the equity.

In 2022 sales were $98 million, operating income was $22 million owing to lower operating expenses, operating cash flow was also $22 million, or $17.6 million after taxes, minus $4.8 million in noncontrolling interest, leaving $12.8 million for the equity.

As I stated, there are several share classes: 6.2 million shares of common stock, 382.5 thousand shares of the class C controlling stock that has the equivalent of 9.6 million votes, as well as 146 class B shares that seem to exist for nostalgic purposes, and 313.4 thousand preferred shares. The class C shares are individually entitled to just under 1/3 of the dividends paid on the common shares (although the company doesn’t pay dividends and with 2/3 of its market cap being excess cash the company has kind of painted itself into a corner in this regard), and are also convertible into common shares at a ratio of 1 common shares per 3 class C shares. The preferred stock ranks equally with the common shares in terms of dividends, distributions, etc. So, at first approximation there are 6.65 million diluted shares.

Many investors, value or otherwise, look to the possibility of a catalyst to unlock latent value. Last July there was a nonbinding proposal submitted by the founders to take the company private, but the offer was not in any sort of detail and the share price seems to have ignored the news completely. It is not unreasonable for a shareholder to worry that the management can use its control to make that cash balance “disappear,” and more looking into compensation will be in order, but under Delaware law majority shareholders are required to treat the minority shareholders fairly.

Unfortunately, the inability of any outsider to force a change in control of a privately controlled company like FONAR makes the catalyst of a buyout unavailable. I am reminded of a tale of the venerable Benjamin Graham who, in the old days, came upon a railroad company that owned a portfolio of Treasury bonds whose value exceeded the market cap of the entire company. He contacted the management, suggesting that they sell them off and declare a special dividend to see what the market would make of a company with a negative share price. However, the management rebuffed him, saying “If you don’t like how we run our company, feel free to sell your shares.” At which point Graham replied “I don’t want to sell my shares; I want to buy more shares. In fact, I want to buy so many shares I take over the entire company, just so I can fire you.” This didn’t happen, but Graham did get hold of a major shareholder who was able to make them see things Graham’s way for the benefit of all involved.

However, with voting control of FONAR securely locked away, this scenario is unavailable. So it may be that an entrenched management is in the nature of an anti-catalyst. Even so, basic finance teaches us that a company is worth the money it has plus the present value of the money it will have, and the money a company has belongs to the shareholders whether or not it is being given to them in the form of dividends or share repurchases. And at some point the market will have to recognize a company’s cash balance, before or after that balance exceeds the market cap of the company (which in FONAR’s case should take about four years).

The chief risk is that FONAR’s management will manage to siphon off that cash balance in a way that a suit under Delaware law would not be worth the money, and indeed the CEO owns three of their client MRI clinics and they are also owned by outside investors whose identities may or may not be other affiliates of FONAR’s management. Also, for somewhat infuriating reasons the company has been a week or two late with the 10-K for many years and the auditors last expressed critical concern about internal controls. At any rate, direct compensation for Timothy Damadian, who owns nearly all the class C shares, has been a fairly reasonable 295k in 2005, 373k in 2024, and 153k in 2023. I should also point out that cash distributions to noncontrolling interests exceeded their share of net income by $3.7 million in 2025, $2.1 million in 2024, $3.0 in 2023, and $1.0 in 2022, and I would appreciate an explanation for this, but it hasn’t been enough to prevent the cash from building up over the years.

So, unless I’m already missing something, FONAR offers a compelling earnings yield and even without a catalyst the cash buildup will have to be recognized by the market at some point. So, for investors with some patience and willingness to deal with very small cap companies, this is an interesting candidate for portfolio inclusion.