As I stated last week, I have taken the view of James Montier that a low price/sales ratio is an unreliable indicator of cheap stocks, since it ignores profit margins and capital structure. I have similarly adopted his view that an astronomically high price/sales ratio is a reliable indicator of overpriced stocks, because at a certain point there is no capital structure or profit margin that will justify the current price. Furthermore, the degree of growth required to justify a company at that price would be almost impossible to realize. And it seems to me that with Red Hat Inc. (RHT), we have a company in such a situation.

Red Hat Inc. provides software support services for open-source Linux programs in the enterprise space, including product delivery, problem resolution, ongoing corrections, enhancement and corrections, new versions, and compatibility issues, as well as providing training. Their best-known product is the Red Hat Enterprise Linux operating system, and they also include a virtualization platform (which may explain some of the optimism surrounding the company; VMware trades at a similarly high valuation), as well as middleware tools. All their products are open-source rather than proprietary; their revenue, apart from training, comes from the support they provide, which is sold on a subscription basis.

The business model is an attractive one and seems to be effective, no doubt, but Red Hat’s valuation seems to come straight from 1999; they have a price/sales ratio of 9.96 and a P/E ratio of 85. Those figures have recently increased by a 10% reaction to the firm’s 2nd quarter earnings announcement that sales increased 20% year over year and operating earnings increased 23% over the same period. In the current economic environment, such a level of growth is indeed impressive, and the open source model is enhanced by an army of tinkerers inside and outside the company. All of that makes for a good story, true, but as Damodaran reminds us in The Dark Side of Valuation, prudent investing calls for all stories to be translated into numbers.

The business model is an attractive one and seems to be effective, no doubt, but Red Hat’s valuation seems to come straight from 1999; they have a price/sales ratio of 9.96 and a P/E ratio of 85. Those figures have recently increased by a 10% reaction to the firm’s 2nd quarter earnings announcement that sales increased 20% year over year and operating earnings increased 23% over the same period. In the current economic environment, such a level of growth is indeed impressive, and the open source model is enhanced by an army of tinkerers inside and outside the company. All of that makes for a good story, true, but as Damodaran reminds us in The Dark Side of Valuation, prudent investing calls for all stories to be translated into numbers.

Ultimately, reported earnings were down from a year ago, which the company blames on amortization and stock-based compensation. Now, as it appears that Red Hat’s stock is very expensive, the company is probably better off paying its staff in stock rather than cash. However, from the perspective of a shareholder, dilution is still dilution, and so their removal of stock-based compensation to arrive at their pro-forma earnings seems a little like cheating to me.

Turning to the amortization, however, I prefer to eliminate depreciation and amortization and replace it with capital expenditures in order to get closer to determining free cash flow for the period. From that perspective, Red Hat claimed total depreciation and amortization of $11.7 million, and total capital expenditures of $9.7 million last quarter, which would increase quarterly earnings to $25.7 million. The comparable figure for last quarter would be $32.7 million, after making an adjustment of $3.7 million for the same reason.

However, considerable further adjustments have to be made to strip out the Red Hat’s non-operating income and expense and to address the issue of deferred revenues in order to enable a real history of earnings growth. It is a somewhat labor-intensive process, but necessary in my opinion, to arrive at figures that most readily permit year-over-year comparisons and to arrive at a calculation of what the owners of the company are actually getting out of it (and therefore what the shorts would have to cough up).

The first necessary adjustment is often to separate a company’s core operations from their non-operating income and expenses. In Red Hat’s case these adjustment are significant, because Red Hat has a vast portfolio of cash and securities that composes the bulk of its balance sheet. It also has currency translation issues as the firm does business in multiple regions. As interest rates are lower this year than last, it would be reasonable to eliminate interest, gains on trading in securities, and currency translation, to make the two periods comparable.

Now, it may be objected that I want to take out interest and trading profits because I’m approaching this situation from the short side and as a result I want to make the figures look as bad as possible. However, I would reply that even if the company may be entitled to a high multiple, their cash and investable securities are not. Their portfolio certainly doesn’t become magical because they own it. So, if we separate the $1.05 billion in cash and securities on Red Hat’s balance sheet, and treat it separately from the remaining $6.66 billion price, we get closer to looking at the value of Red Hat’s core operations.

Now, it may be objected that I want to take out interest and trading profits because I’m approaching this situation from the short side and as a result I want to make the figures look as bad as possible. However, I would reply that even if the company may be entitled to a high multiple, their cash and investable securities are not. Their portfolio certainly doesn’t become magical because they own it. So, if we separate the $1.05 billion in cash and securities on Red Hat’s balance sheet, and treat it separately from the remaining $6.66 billion price, we get closer to looking at the value of Red Hat’s core operations.

This means lowering the 2nd quarter fiscal year 2011 earnings by $2.3 million, and the 2010 earnings by 5.7 million, to reflect interest, trading, and currency translation income. I should also note that 2010’s 2nd quarter tax rates were unrealistically low and should be adjusted. Taking $2.3 million out of pretax earnings and applying a standard 35% tax rate, 2011’s 2nd quarter “core” earnings were $22.2 million, and after a similar adjustment to 2010’s earnings we see “core” earnings of $17.9 million. Adding back in the difference between depreciation and expenditure calculated above, we get “core” free cash flow estimates of $24.2 million for 2nd quarter 2011, and $21.6 million for 2nd quarter 2010. So, at the end of this laborious process we have found that their core operational earnings growth is 12% over last year.

If we apply a similar adjustment process (eliminating interest and other income, applying a standard 35% tax rate, and adding back in depreciation but removing capital expenditures) across the last three years’ results, we find 2010’s full year “core” results were $81.8 million, 2009’s were $62.4 million, and 2008’s were $27.3 million (although capital expenditures that year seem unusually high). So the growth is there, but it’s slowing (12% as compared to the year-ago quarter, down from 31.1% 2010 as compared to 2009 and 128% as compared to 2008, which, again, may be distorted by capital expenditures).

Turning now to the deferred revenue issue, Red Hat produces cash flow greater than its earnings because it sells year-long or multi-year subscriptions. The firm recognizes the revenue over the lifetime of the contract but on the whole likes to be paid a significant amount up-front. The cash that the subscribers pay in advance shows up on the cash flow statement and the balance sheet (offset by a liability for deferred revenue, of course), but it would be most unwise to consider it “free money.” Not only do those payments have to be earned by Red Hat providing the direct costs of the services that were subscribed, which costs money, but also they should bear their fair share of the cost of running the company, including administration, marketing and research and development. The deferred revenues should also bear their fair share of taxes, since the revenue most definitely will be taxed when it is recognized.

If we prorate these expenses between revenues recognized and deferred revenues, we can compute the effective operating margins for their core operations, and if we then apply these margins to deferred revenues we will be pretty close to calculating the company’s core free cash flow, which is what is needed to perform a sensible valuation in the first place.

In fiscal year 2008, the core after-tax operating margin including deferred revenues was 16.4% and accordingly we add 16.4% of their deferred revenues to their 2008 core earnings, producing a total estimated core free cash flow from operations of $42.2 million. In fiscal year 2009 the margin was 17.2% and adding back in that amount of deferred revenues gives us estimated core free cash flow of $79.3 million, and in fiscal year 2010 the margin was 16.5%, so adding back in that proportion of deferred revenue we get $95.4 million. This gives us growth rates of 73% between 2008 and 2009, and 20.4% between 2009 and 2010. Performing a similar calculation for 2nd quarter of 2011, we get core margins of 14%, giving us core free cash flow of $26.1 million, as compared to a margin of 14.5% and core free cash flow of $23.1 for 2nd quarter 2010. This gives us 13% growth, in line with what we calculated above. Fortunately the margins are stable enough not to produce a major distortionate effect.

I will also note that deferred revenues have been declining on the statement of cash flows since fiscal year 2008, which is indicative of deceleration of the growth rate of subscriptions.

Now, growth rates comparing one period to another give us the situation relative to how it was, but if we want to decide if a company is ultimately overvalued or not we have to use absolute measures, and our calculation of core free cash flow serves us well here. We already have the figure for the 2nd quarter of 2011, and calculating it for the prior three quarters we have current core free cash flow of $99.8 million. When set against the $6.66 billion price the market is putting on Red Hat’s core operations, we have a P/E ratio of 66.7. So it is clear that the market is pricing in a high level of future growth.

How high, exactly? Well, let us use the H-model I have previously discussed. The H Model assumes that a company will grow at a high rate that will decay in a linear fashion to a stable growth rate (most companies show growth decay in a faster than linear fashion, actually). In The Dark Side of Valuation, Damodaran calculates that even starting from the IPO, median growth levels decay exponentially until by year 6 the company’s growth rate is indistinguishable from the other companies in its sector. So, six years is a good starting assumption.

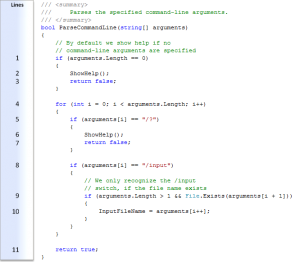

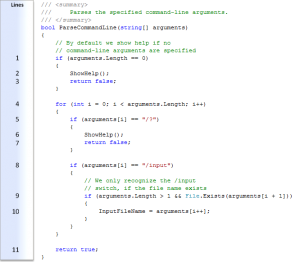

The H model, in case you were wondering, is price = e*(1 + g)/(K-g) +e*H(G – g)/(K – g), where

e = current earnings

g = long-term stable growth rate

G = initial high growth rate

K = required return on equity investments

H = half the number of years until stable growth rate is reached.

Let us make some optimistic assumptions about Red Hat’s future growth. The initial growth rate is set at 30%, much higher than it is now. If 6% is the long term growth rate of Red Hat’s target market (generous but not unreasonable, as it takes into account both inflation and actual growth), and using the six year assumption and a required return of 10%, we get a total value for the core cash flows of the firm of $4.4 billion, far below the $6.66 billion price tag. In order for the company to grow into its valuation, then, either the initial growth rate has to be set at around 60%, or the high growth period has to last for 13 years instead of 6, neither of which I find particularly likely considering that growth is already showing signs of slowing.

I do not know what the reason for the optimism regarding Red Hat Inc.’s share price; there is always surely some residual love of technology at work in the investment community, and also perhaps people are looking at the gross margin of the subscription business, which is over 93% last quarter. However, the subscription business cannot be capable of limitless growth, particularly without the marketing, administrative, and research and development expenses necessary to support an expansion. Therefore, I find it highly unlikely that this company can produce the kind of growth necessary to justify its valuation. And so, although the company is operationally stable and does not seem to have any catalyst that would instigate a price drop, I can see ample grounds for considering it a short candidate.

I do not know what the reason for the optimism regarding Red Hat Inc.’s share price; there is always surely some residual love of technology at work in the investment community, and also perhaps people are looking at the gross margin of the subscription business, which is over 93% last quarter. However, the subscription business cannot be capable of limitless growth, particularly without the marketing, administrative, and research and development expenses necessary to support an expansion. Therefore, I find it highly unlikely that this company can produce the kind of growth necessary to justify its valuation. And so, although the company is operationally stable and does not seem to have any catalyst that would instigate a price drop, I can see ample grounds for considering it a short candidate.