The New York Times Indicator

John Maynard Keynes described speculation as essentially trying to guess what other people are going to guess, and doing it better than they guess how you’re going to guess. I think this also describes macro-level investing, i.e. allocating capital based on economic data. As I stated in my last article, focusing on a decent cash flow avoids many of the problems that come from market correlation, leaving you with only the strength of your own analysis to worry about. However, the New York Times has given us a macro indicator that even the most cynical and suspicious of us can get behind. And it’s not even in their business section.

It is, in fact, the New York Times Bestseller List. In a classic investment comedy book, Rothchild’s A Fool and His Money, the author found a newsletter that went through the bestseller lists, and found that the optimum strategy was to peruse the lists for finance and investment books and then do the exact opposite of what the books recommend:

It is, in fact, the New York Times Bestseller List. In a classic investment comedy book, Rothchild’s A Fool and His Money, the author found a newsletter that went through the bestseller lists, and found that the optimum strategy was to peruse the lists for finance and investment books and then do the exact opposite of what the books recommend:

“In the early 1920s Edgar Lawrence Smith wrote…Common Stocks as a Long Term Investment. This book was ignored during the entire period when it would have been a good idea to buy stocks. Suddenly it became a best-seller in 1929…During the entire period from 1932 to 1967…not a single investment book became a best-seller…until Adam Smith’s Money Game was published in 1968, after which the stock market promptly topped out and collapsed. In 1974 Harry Browne’s You Can Profit from a Monetary Crisis…turned half the reading public into gold hoarders, and was followed by a severe decline in the price of gold. Gold didn’t rise again until there were no gold books on the best-seller list…Then it hit $800 an ounce. In the early 1980s, several national bestsellers (most notably Howard Ruff’s How to Prosper During the Coming Bad Years) predicted high inflation forever…a sure sign that inflation had abated. Later in the decade, Jerome Smith’s wildly popular book The Coming Currency Collapse, a terrifying rationale for the total collapse of the US dollar, sold out several editions just as the dollar began its remarkable three-year bull market. Megatrends, a summer favorite in 1983, predicted the triumph of high technology and pronounced the smokestack industries dead. Along…came a genuine depression in the microchip and computer industries and a huge drop in the value of technology stocks, while smokestack industries revived.â€

The book was published in 1988, but a sequel would bear up this conclusion. During the dot-com era, Dow 36,000 was published in 1999. The next year the Dow hit 11,750 and then fell to 7286, hit an all-time high of 14164 in 2007, and it looks right now like 36000 is decades of inflation away. And, who could not have predicted the death of the real estate market from the popularity of the Rich Dad series? In 2007 one of Amazon.com’s bestselling books was Bogle’s Little Book of Common Sense Investing, which advised focusing solely on index funds, right before the indexes collapsed, prompting a swarm of articles about a negative return over ten years (although counting from a bubble to a collapse is kind of cheating).

Right now the New York Times list is devoid of financial books, which is tentatively a good sign for the financial public. Although Rothchild and his newsletter deemed it significant that books on a given subject were not on the list, I think the presence of a book is more important than its absence. #19 this week, however, is Fareed Zakaria’s The Post-American World, about the rise of China and India and the global middle class. It is more optimistic than the title would suggest (and why not? It was first published in April 2008 when the world was better stocked with optimism).

As an aside, China has pegged its currency to the United States dollar for a number of years, in order to perpetuate the trade deficit and build up a substantial pile of Treasury holdings. We ran the price of oil up to $140 a barrel just to shake them off, and now they have the flaming nerve to complain about inflation and suggest that the world needs a new reserve currency. Interestingly, that article also talks about China seeking to switch from export dependency to internal consumption. The trouble is that China’s rapid growth built half of an economy, with the United States and its other importers providing the other half. Since demand creates supply, but supply does not create demand, it’s fairly clear who got the right half. So, for everyone worried about the decline of America’s economic influence, rest assured that when we go down we can still take the rest of the world with us. And, if the New York Times indicator works true to form, the global middle class is doomed anyway.

As an aside, China has pegged its currency to the United States dollar for a number of years, in order to perpetuate the trade deficit and build up a substantial pile of Treasury holdings. We ran the price of oil up to $140 a barrel just to shake them off, and now they have the flaming nerve to complain about inflation and suggest that the world needs a new reserve currency. Interestingly, that article also talks about China seeking to switch from export dependency to internal consumption. The trouble is that China’s rapid growth built half of an economy, with the United States and its other importers providing the other half. Since demand creates supply, but supply does not create demand, it’s fairly clear who got the right half. So, for everyone worried about the decline of America’s economic influence, rest assured that when we go down we can still take the rest of the world with us. And, if the New York Times indicator works true to form, the global middle class is doomed anyway.

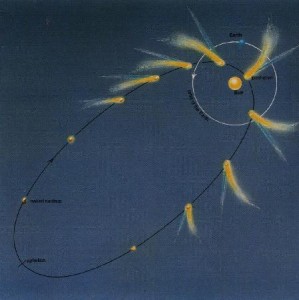

Obviously, when the market is in a depressed mood bargains are more likely to be available, but the central tenet of value investing is that a security’s price and value behave like a comet orbiting a star; they’re locked together as if by gravity but only on rare occasions are they close. However, it is the nature of all financial assets that they turn into cash sooner or later; for bonds, it’s not only sooner but according to schedule, for stocks, often but not always later because they are constantly selling, buying, and shuffling around assets.

Obviously, when the market is in a depressed mood bargains are more likely to be available, but the central tenet of value investing is that a security’s price and value behave like a comet orbiting a star; they’re locked together as if by gravity but only on rare occasions are they close. However, it is the nature of all financial assets that they turn into cash sooner or later; for bonds, it’s not only sooner but according to schedule, for stocks, often but not always later because they are constantly selling, buying, and shuffling around assets. Compass Minerals operates a number of salt mines, and sells rock salt for road de-icing and more refined salt for industrial purposes and consumption by humans and animals. They also produce potash fertilizers. Compass claims to be one of the lowest cost salt providers in the nation, and in the last three years has produced excellent earnings growth, although last year’s high earnings may have something to do with the

Compass Minerals operates a number of salt mines, and sells rock salt for road de-icing and more refined salt for industrial purposes and consumption by humans and animals. They also produce potash fertilizers. Compass claims to be one of the lowest cost salt providers in the nation, and in the last three years has produced excellent earnings growth, although last year’s high earnings may have something to do with the  Antitrust laws in the US forbid generally any attempt to monopolize, and this includes attempting to maintain a monopoly by any means other than competition on the merits, including a refusal to deal with competitors. Assuming that some clever economist expert witness can conclude that this denial will harm competition, 20th Century Fox can still easily claim that they have the legitimate business reason of protecting the perceived value of their own products in the marketplace. There is broad support for the view that antitrust law permits holders of intellectual property to unilaterally refuse to license it. After all, the Constitution provides for temporary monopolies for patents and copyrights, and although this does not provide a blanket immunity for antitrust actions (just ask Microsoft), most legal commentators allow them to retain that monopoly as long as they do not try to leverage it into a non-monopolistic area, although the 9th Circuit has ruled that even this is permissible unless the owner is “not actually motivated by protecting its IP rights.†Since they have a legitimate business reason, which they seem to, they should be in a fine position for this suit. There is caselaw to suggest that there is a heightened standard for situations where a monopolist refuses to sell a product to one competitor that it makes available to others, or has done business with a competitor and then stops, but this seems to be more of an indicator of monopolistic action than anything imposing a higher legal standard, and a legitimate business reason will still defeat it. There is also case law to the effect that there is no difference between selectively granting a license and refusing to grant it all, so no worries to Fox and Universal on that front.

Antitrust laws in the US forbid generally any attempt to monopolize, and this includes attempting to maintain a monopoly by any means other than competition on the merits, including a refusal to deal with competitors. Assuming that some clever economist expert witness can conclude that this denial will harm competition, 20th Century Fox can still easily claim that they have the legitimate business reason of protecting the perceived value of their own products in the marketplace. There is broad support for the view that antitrust law permits holders of intellectual property to unilaterally refuse to license it. After all, the Constitution provides for temporary monopolies for patents and copyrights, and although this does not provide a blanket immunity for antitrust actions (just ask Microsoft), most legal commentators allow them to retain that monopoly as long as they do not try to leverage it into a non-monopolistic area, although the 9th Circuit has ruled that even this is permissible unless the owner is “not actually motivated by protecting its IP rights.†Since they have a legitimate business reason, which they seem to, they should be in a fine position for this suit. There is caselaw to suggest that there is a heightened standard for situations where a monopolist refuses to sell a product to one competitor that it makes available to others, or has done business with a competitor and then stops, but this seems to be more of an indicator of monopolistic action than anything imposing a higher legal standard, and a legitimate business reason will still defeat it. There is also case law to the effect that there is no difference between selectively granting a license and refusing to grant it all, so no worries to Fox and Universal on that front. Copper penny enthusiasts

Copper penny enthusiasts Inflation, of course, is simply an increase in the money supply that outpaces an increase in the size of the economy (actually, that’s stagflation, but stagflation is really the pernicious aspect of inflation). The purpose of money is to facilitate transactions, and as the number of transactions increases the size of the money supply should increase accordingly. Now, of course, the economy has shrunk even as all this stimulus is being thrown at the market, and we are still worrying about deflation. This implies one of two things, either that inflation is going to come later, or that the inflation has been avoided.

Inflation, of course, is simply an increase in the money supply that outpaces an increase in the size of the economy (actually, that’s stagflation, but stagflation is really the pernicious aspect of inflation). The purpose of money is to facilitate transactions, and as the number of transactions increases the size of the money supply should increase accordingly. Now, of course, the economy has shrunk even as all this stimulus is being thrown at the market, and we are still worrying about deflation. This implies one of two things, either that inflation is going to come later, or that the inflation has been avoided. Rayonier owns 2.6 million acres of timberland, and also produces lumber and wood products, and wood fibers for hygiene products and also specialty fibers for industrial use running the gamut from packaging to LCD displays. Naturally the decline in demand for construction materials has hurt them, but even at this low ebb of their business, they have managed to squeeze out at least $25 million in earnings per quarter lately. Their free cash flows are approximately equal to their dividends, currently yielding 5%. This puts them at risk of a dividend cut, but for inflation hedging purposes this is not really relevant, as it is better to keep the money in the firm to buy more timberland with in that event.

Rayonier owns 2.6 million acres of timberland, and also produces lumber and wood products, and wood fibers for hygiene products and also specialty fibers for industrial use running the gamut from packaging to LCD displays. Naturally the decline in demand for construction materials has hurt them, but even at this low ebb of their business, they have managed to squeeze out at least $25 million in earnings per quarter lately. Their free cash flows are approximately equal to their dividends, currently yielding 5%. This puts them at risk of a dividend cut, but for inflation hedging purposes this is not really relevant, as it is better to keep the money in the firm to buy more timberland with in that event. Rayonier also is getting a nice little bonus from the tax system this year from black liquor, a byproduct of the fiber refining process that contains the nonfibrous parts of the wood and the leftover chemicals used in the process. The refining of wood into wood pulp for their fiber business produces some nice long usable fibers, and a great deal of black slime. A highly toxic black slime. When dried, a highly flammable black slime. When dried and mixed with a bit of diesel fuel, a highly lucrative black slime, since the government pays a subsidy of 50 cents a gallon for its use under an alternative energy program. The program expires at the end of this year, and there is a movement in Congress to cut off the eligibility of pulp mills immediately, on the grounds that black liquor is not really an alternative fuel. (It has been used since the 30s and nearly every pulp mill uses it, meaning that it is not an “alternative” to anything.) To date this year, Rayonier has benefited $86 million from this subsidy, and there are two more quarters. Since the program will expire if not extended (which extension is not outside the realm of possibility), we cannot count on this $43 million a quarter as part of the firm’s operating income, but it is a nice little enhancement that will cushion the blow of the business slowdown for the moment.

Rayonier also is getting a nice little bonus from the tax system this year from black liquor, a byproduct of the fiber refining process that contains the nonfibrous parts of the wood and the leftover chemicals used in the process. The refining of wood into wood pulp for their fiber business produces some nice long usable fibers, and a great deal of black slime. A highly toxic black slime. When dried, a highly flammable black slime. When dried and mixed with a bit of diesel fuel, a highly lucrative black slime, since the government pays a subsidy of 50 cents a gallon for its use under an alternative energy program. The program expires at the end of this year, and there is a movement in Congress to cut off the eligibility of pulp mills immediately, on the grounds that black liquor is not really an alternative fuel. (It has been used since the 30s and nearly every pulp mill uses it, meaning that it is not an “alternative” to anything.) To date this year, Rayonier has benefited $86 million from this subsidy, and there are two more quarters. Since the program will expire if not extended (which extension is not outside the realm of possibility), we cannot count on this $43 million a quarter as part of the firm’s operating income, but it is a nice little enhancement that will cushion the blow of the business slowdown for the moment. USEC Inc. has an interesting one; a loan guarantee from the Department of Energy that they applied for in order to construct a new facility. USEC is currently the only uranium refinery operating in the United States. It turns mined uranium into low enriched uranium for use in nuclear power plants, and presently employs archaic and inefficient gaseous diffusion technology. Ironically, one of the biggest inputs to producing fuel for electric plants is electricity; 65% of USU’s operating costs come from electricity, and centrifuge technology requires an impossible-seeming 95% less power. For this reason, most nuclear fuel enrichers have switched over to centrifuge technology, and USU wants to open a new plant in order to join them.

USEC Inc. has an interesting one; a loan guarantee from the Department of Energy that they applied for in order to construct a new facility. USEC is currently the only uranium refinery operating in the United States. It turns mined uranium into low enriched uranium for use in nuclear power plants, and presently employs archaic and inefficient gaseous diffusion technology. Ironically, one of the biggest inputs to producing fuel for electric plants is electricity; 65% of USU’s operating costs come from electricity, and centrifuge technology requires an impossible-seeming 95% less power. For this reason, most nuclear fuel enrichers have switched over to centrifuge technology, and USU wants to open a new plant in order to join them.