Warren Buffett famously said that investment opportunities arise when a business faces a large but solvable problem. However, how can an investor be sure that a problem is solvable until it’s been solved? And once the market consensus is that it has been solved, the stock price can be expected to reflect the fact that it has been solved, making the stock no longer a bargain.

This brings us to Ingevity, a chemical company that has been confronting a steep rise in a key input material that has resulted in substantial and expensive restructurings. The company is projecting that these changes will return the company to profitability and stability, and if their views are correct the company offers an attractive prospect at the current price. However, the company’s sales are under pressure even if the restructuring is effective, and if that is the case, it is possible that management’s projections can be disappointed.

Ingevity produces various carbon products from plant sources. It operates in three divisions: performance materials, which makes activated carbon products for internal combustion engines designed to capture gasoline vapor and return it to the engine, thus simultaneously improving fuel efficiency and pollution. Performance materials also comprises various carbon filters. Their second line of business, and the problematic one, is performance chemicals, which produces road surfacing and also a hodgepodge of chemicals for glue, ink, paper finishing, and emulsifiers for oil drilling. The problem is that prior to this year, the company’s main input for these products has included crude tall oil (CTO), which is a byproduct of making paper out of pine wood, which represented 26% of total cost of sales and 51% of its raw materials. Until very recently, Ingevity was locked into a long term supply contract while the price of CTO has risen dramatically, partly as a result of a decline in paper manufacturing, and was unable to pass this increased cost on to their customers. The company has since made considerable efforts to switch over to soy, canola, and palm oil, and to negotiate a way out of the supply contract at considerable expense. However, this restructuring will reduce the company’s exposure to the its miscellaneous chemical products, allowing it to focus on paving, charcoal filters, and its third division. The company claims that these miscellaneous product lines are low margin (negative margin, actually, because of the CTO problem), but still, profits are profits. Their third division, advanced polymers, produces caprolactone-based specialty polymers for use in coatings, resins, elastomers, adhesives, bioplastics, and medical devices (obviously I’m not an organic chemist).

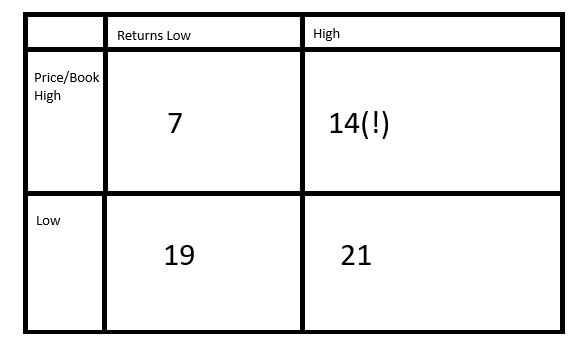

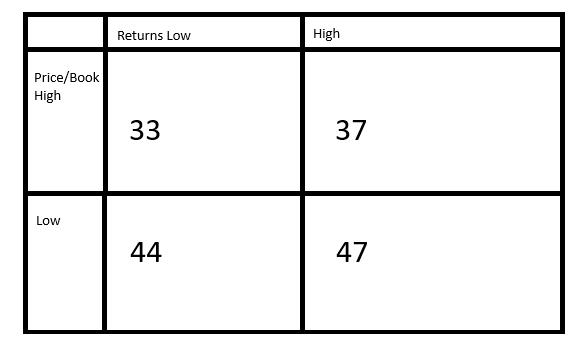

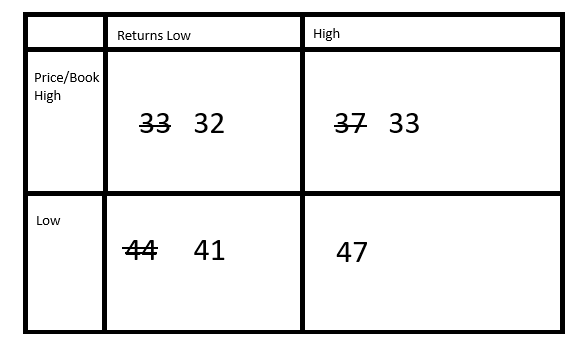

As of this writing, the company’s market cap is $1.4 billion. The figures we have to work with are:

In fiscal year 2023, sales were $1692 million, operating income was $256 million before restructuring charges, interest expense of $99 million, leaving $157 million, or $124 million after estimated taxes. There is also $13 million in excess depreciation, resulting in $137 million in free cash flow, adjusted for restructuring charges.

In 2022, sales were $1668 million, operating income $341 million, interest expense $62 million, leaving $279 million in income, or $220 million after estimated taxes, before $32 million in capital expenditures in excess of depreciation, leaving $188 million. The company would like to chalk much of the difference up to the spike in CTO costs, and indeed cost of goods sold for the specialty chemicals did increase by $157 million between 2022 and 2023, while sales in every division except their miscellaneous industrial chemicals improved in 2023.

In 2021, sales were $1391, operating income was $307 million, interest expense was $51 million leaving $256 in pretax income or $202 million after taxes, and depreciation closely tracked capital expenditures.

Sorting out the projected effects of Ingevity’s restructuring involves going through a lot of SEC filings. The company has projected $250 million in writeoffs and restructuring charges, of which $70 million will be in cash. Of this amount, $25 million has already been recognized, and $25-$35 million more will be recognized in the remainder of 2024. But on the upside, the restructuring is expected to contribute a projected $30-35 million annually to the bottom line. As a result of this restructuring, the company also was forced by its supply contract to purchase vast amounts of CTO that it no longer required and had to sell into the open market, which resulted in a $50 million loss in 2023, which the company very kindly included in non-operating activities so it would not affect the free cash flow estimates above.

Furthermore, in July of 2024, conveniently just after the second quarter financials were filed, the company reported that they spent $100 million to finally get out of the CTO supply contract. Also, Ingevity is consolidating two manufacturing plants, which will cost a further $135 million in restructuring, of which $35 million is in cash, but which will, according to their projections save them $95-110 million in expenses, but 70-80% of that represents cost of sales and is therefore not accretive to earnings. At any rate, if we keep a price/sales ratio of 1 and a required return on investment of 10%, the costs of the restructuring and the savings produced by it seem to be roughly in line, if Ingevity’s management projections can be trusted. But at any rate, it is refreshing to see management being capable of such bold moves affecting such a large portion of their operations

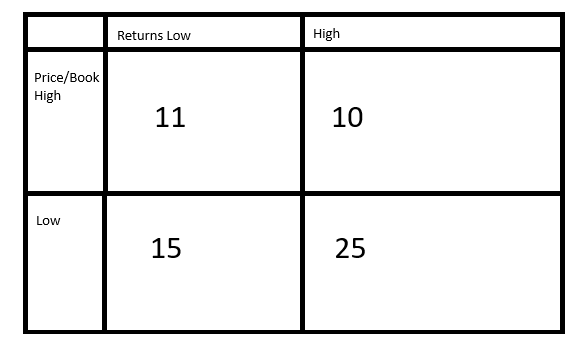

So, in this difficult transitional year, for the first half of 2024 net sales were $731 million vs $874 last year, operating income was $120 vs $166, interest was 45 vs 41, leaving 75 vs 125 or 59 vs 99, and excess depreciation of $18 vs $15, resulting in estimated free cash flow from operations of $77 vs $114.

I should point out that based on the second quarter earnings call, the company was projecting $75 million in free cash flow for the entire year before the contract termination fee, although this figure did include $45 million in cash from CTO sales that are not expected to recur. Even so, I note that the $114 million for 2023 is already the bulk of the company’s free cash flow for the entire year. This is not surprising, as road surfacing is a seasonal business and most of the purchases take place between April and September apparently. I should also point out that excess depreciation may be unreliable, as many of what would under normal circumstances be new capital expenditures on the non-CTO-using product lines have been filed under the heading of restructuring charges and therefore deemed nonrecurring.

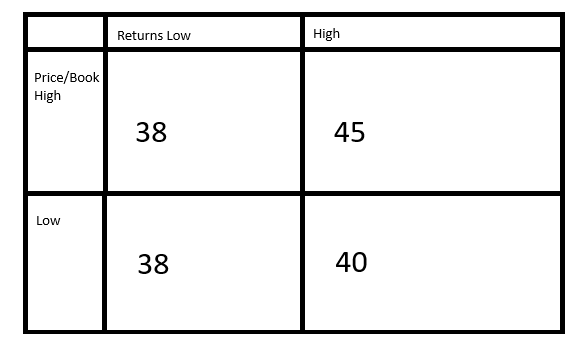

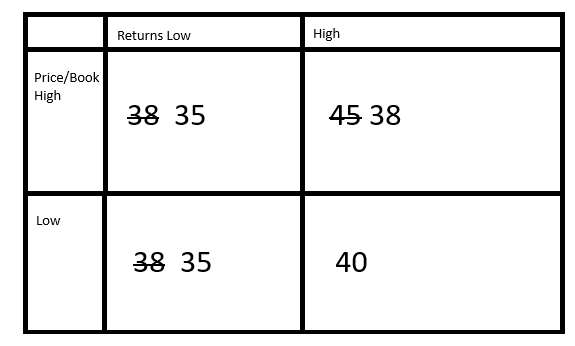

That same earnings call suggested that management was projecting free cash flow of $150 million for 2025, which seems to be achievable if the restructuring proceeds according to plan. However, although automotive products and carbon filters showed growth in 2024, road surfacing showed slight declines and so did industrial polymers, and of course the miscellaneous chemicals showed significant declines as the company has already stated it is transitioning away from these areas. So, even if the CTO-related problems have been solved, Ingevity may have some difficulty in controlling its pricing and margins, which can derange projections. Moreover, whenever I compare a company’s estimate of its free cash flow to my own calculations, theirs always comes in a little higher for some reason.

So, is the market consensus that the problem has been solved? Well, as of this writing the share price is near a multi-year low at $38.60, having fallen there from a peak of $90 at the beginning of 2023 when this CTO problem emerged. However, the share price fell to $38 in October of 2023, drifted back up to $54 last May, and then fell back to the $35s with the latest earnings announcement. Interpreting investor sentiment from price movements is a speculative business at best, but the decline from the latest earnings suggests that market believes that nothing has been solved yet, or that the cost of getting out of the CTO contract was disappointingly high. However, if the market does buy the figure of $150 million as a reasonable estimate of Ingevity’s free cash flow generation in the future, and sticks with a 10% return on investment as a reasonable figure given the company’s somewhat weak pricing power and ability to pass costs of input on to its customers as offsetting potential growth in investments, then the company seems reasonably priced as of now, and any shift in a positive direction might result in price increases.

Wherefore, I cannot recommend this as a pure value investment as it seems to be not in a strong competitive position and much of its value proposition depends on the management’s projection of the effectiveness of its restructuring. However, as a speculation, there are certainly worse opportunities out there.